|

First Cast...

from Honey Hole Magazine - Aug/Sept/Oct 2002 issue |

32 days on the Clear Fork of the Brazos River

|

First Cast...

from Honey Hole Magazine - Aug/Sept/Oct 2002 issue |

Arid land,

meaning insufficient rainfall not necessarily desert, lies only a short distance

from the river's banks. The settlers who came before us to ranch or farm had no

stock tanks or windmills at that time. What they did have was constant flowing,

clean water in this tributary of the Brazos River. As far as we know, the Clear

Fork received its name not because it was clear sparkling water, but because the

other tributaries (Salt and Double Mountain) of the Brazos contain heavy amounts

of gypsum and other salts leaving their water brackish and unpalatable to man

and animal alike. The current erosion problems, caused by overgrazing which

certainly hasn't helped the amount of silt carried downstream after every rain,

were not present in the 1850's. Written accounts of the Clear Fork still

described it sometimes as red and muddy. Prior to the growth of civilization we

have now, as well as the consequent reckless consumption of water that comes

with it, and before the still spreading overgrowth of both salt cedars and

mesquite trees, this section of Texas had numerous underground springs which

flowed to the surface. Not only the river itself, but most of the creeks shown

on our map (next page) held a continuous discharge of life-giving liquid. Thus

the Clear Fork became a major trail for settlers and others headed west, or

southwest, through northern Texas - the same as it had for prehistoric man,

Indians, and the Spanish explorers who sought both food and water in their day

to day struggle to survive the harsh environment in which they lived and

traveled through.

In our desire to seek adventure, as well as outline the

history of this relatively small but important part of Texas, Bob Hood and I

chose to follow the course of this same river. Those before us walked on foot,

rode on horseback, or in wagons, following and sometimes crossing at shallow

fords in the stream since canoes were seldom used in this part of the country.

We wanted to see more of it up close. We wished to feel the history. We wanted

to follow the river's course that brought life to this part of our

state.

Why Bob and I chose the Clear Fork for an extended canoe trek is

almost a story in itself, and will be explained shortly. We'll tell you how this

trip came about at the end. Here at the beginning I'll tell you that it ended

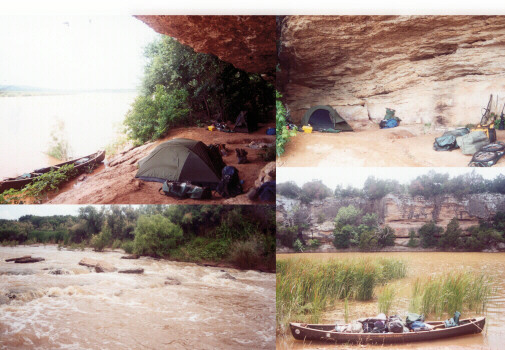

successfully after 32 days of hardship and struggle. Days-on-end of hardship

that had us both covered in cuts, scratches, bruises and blisters that soon

turned into hands and feet that were almost completely covered in hard calluses.

We loved (almost) every minute of it.

Join us on this true adventure that

we are obviously proud and willing to share with you. I promise we won't grow

tired of the telling of the story, if you'll try not to get tired of hearing

about it.

All you need do is turn the page.

Jerry

Dean

President/Editor

|

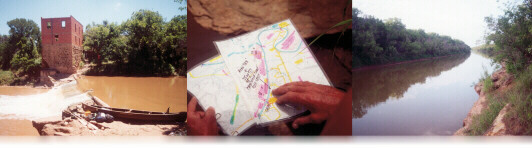

Friends and family waited for us at Possum Kingdom Lake. They asked if we were happy to be home and have it all behind us. The truth is, had someone handed us six gallons of fresh water and rations, we could have kept paddling on towards the Gulf of Mexico. A 32-day wilderness trip will change any individual's outlook on life. You can't help but return home with a better appreciation of what civilization has to offer, the conveniences such as running (clean) water from a faucet, a soft (dry) bed, and (for old men with bad backs) your favorite reclining chair. There is also an almost indescribable feeling of being insignificant. Not a sense of less importance in our day-to-day lives, but a better understanding, or perhaps acceptance, of the power of nature. A thought process occurs that entails a comparison of how small we really are as compared to the forces of nature, such things as wind, rain, and erosion which have and will go on forever. Rising water, even in small flood stages, has a way of making you pay attention. Bob and I experienced this feeling on three separate occasions during our trek. Each time we were made aware that we had to be prepared for the worst, and yet each time it was as if providence had guided our way and the resulting high waters made our excursion easier. It was enough to make a man think about spending more time in church with his creator. |

| Then too,

there's the revelation that sets in when you appreciate the fact that our

predecessors had no GORE-TEX® rain jackets or boots, no battery operated

flashlights, etc., and more importantly, never built a fire, went to sleep or

woke up without wondering if there were hostile Indians nearby. Life was hard.

This narrative of putting in a canoe near the ruins of Fort Phantom Hill at

Abilene and traveling over 230-miles by river to Possum Kingdom Lake holds

little in the way of bass fishing, but like those who went before us there was

seldom time to fish for pleasure. We did catch a bass in Hubbard Creek, which

flows into the Clear Fork near Crystal Falls. Other than that one brief period

of a couple of hours, our time spent fishing was in pursuit of catfish - for

food. Drop-lines were used and baited with the hearts or livers from either

bullfrogs or squirrels, the one meal almost guaranteeing another. While we didn't set out to make this a survival trip, we did limit our food supply to dried fruit and instant oatmeal for almost every breakfast, and the bulk of our other foodstuffs were in the form of freeze-dried vegetables to which we added various species of wild game. We did supplement our dietary needs with carbohydrate and protein bars to furnish ourselves with the needed energy to maintain the high level of exertion required to push and pull our boat through "skinny" water. We also carried several modern MRE'S (Meals, Ready to Eat) used by the military, to fall back on when game was scarce or more to the point, when we did not have the available time to hunt or fish. No different than a backpacking trip, weight taken in a canoe is weight that has to be carried during portages. We toted 355 pounds.

|

|

|

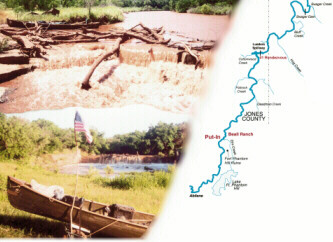

Time, the

same as weight, was important to us on the Clear Fork. It takes time to portage

the 21 dams that cross the river between Abilene and Possum Kingdom Lake. A

couple of the lower manmade obstacles, which have been built to facilitate the

property owners crossing at low water fords, we were actually able to slide over

due to the rise in the rivers flow. Then there were others, some only a few feet

above the rivers surface, that still took several hours to cross. And there were

still others that, to us, looked like Niagara Falls. The three-tier spillway a

short distance west of the city of Lueders was daunting.

|

| This story really began with a fellow by the name of John Graves and a

book he published back in 1960 titled Goodbye to A River. A classic in its own

right, John's book detailed his 21-day trip in 1957 by canoe down the Brazos

River from the dam at Possum Kingdom Lake. His observations on the river, the

land and history that surrounded it, and his thoughts along the way are worth

reading whether you care about paddling a canoe or not. A gifted writer, John's

feelings for "his" river were, and are, strong. I want to thank him publicly for

granting us his time to be interviewed for our TV special. Our good friend Dr. Bill Harvey Ph. D, who works for Texas Parks and Wildlife in the Natural Resource Protection division, duplicated Mr. Graves trip several years ago after reading the book. Bill felt strongly about the Brazos as well since he grew up at a marina his dad owned at Possum Kingdom. Bill and I have camped and fished together out of canoes for a number of years now on several Texas rivers including the Brazos, Colorado and the secluded Devils River at the state park above Lake Amistad. Harvey and I have a close, but unusual relationship in that his education overshadows mine immensely. Still, we share a fondness of the outdoors including wildlife observation and bird watching, a true love of fishing, camping, river exploration and history, which has helped us form a warm friendship. We share deep philosophical thoughts when we're together or even on the phone, and yet he loves to point out when I might happen to use a five-syllable word. Playing and picking at each other is part of the friendship that has developed, so it was natural for me to tell him a couple of years ago that sooner or later I was going to spend 22 days on a river trip just to best his record. I have spent my entire life camping, hunting and fishing, the outdoors is my life. My first boat as a youngster was a wooden pirogue dad traded a .30.30 hex-barreled Winchester for, and I carved my own paddle to scull it with. And although I'll never give up bass fishing on our reservoirs, creeks and rivers were where I learned to fish. Camping out for up to 10 days on several occasions had always been a pleasure, stretching that to 22 didn't seem "undoable." Then last July, when the temperature was actually 107 degrees, I called my buddy Bob Hood and told him I wanted to spend a couple of days canoeing the section of the Brazos where it comes into Possum Kingdom Lake. We regularly do guided canoe trips below PK, but I had never paddled above the lake. Bob, who obviously doesn't know any better than I do to stay out of the sun in the middle of a Texas summer, immediately agreed. It was so hot we made "cold camp" at night, but still enjoyed the trip and each other's company. Somehow Bill's name came up, and the story about a 22-day excursion developed into a plan. Eventually, after scouring books and maps, I found the Clear Fork to be a reasonable choice, except for the fact that it seemed no one had ever made the trip from one end to the other. The reason being was a lack of sufficient water flow. Bob and I talked it over and the plan began to develop. Reasonable or not, we knew we were going to do it. It was our destiny. |

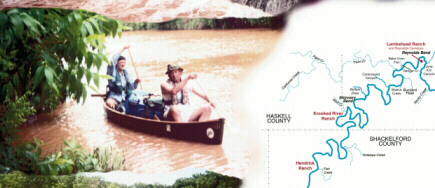

The telling of this story has to include the many new friends we made along the course of the river, people who went out of their way to assist us. There's not nearly the space to tell all the stories and thank all those like Buzz Wylie, Brian Stovall, and Marilyn Beall helping us at put-in. Folks like Joe Don Hicks, Curtis Dawson, Dennis Hill and C.B. Stroud, who helped us at portages. Ranchers John Blue and Zohn Milam who allowed us to rendezvous on their land, as Lester Galbreath, the park manager, at Fort Griffin did. Then there were others who welcomed us on their property like Roy and Becky Wilson who operate Texas Best Outfitters at the Krooked River, Ardon and Rue Judd, John Burns, and John Mathews, descendents of the Lambshead families along with neighbor Linda Perry, John and Janna Caldwell at the Caldwell spread, Lanny and Tonya Vinson just down river, and John Moss at Indian Springs. Sheriffs like John Hobson, and Larry Moore of Jones County whose family has ranched the land since the 1870's, state game wardens like Brian Huckabay and Shea Guinn who were all very helpful. Then, too, there were the sponsors of the trip who helped make it possible, Fishing Hot Spots Maps, Texas Outdoors, Outdoor Texas Adventures, and most of all Miller Distributing of Fort Worth. To each and every one we owe our thanks for their help, support and friendship. For additional information on the trek you can read Bob Hoods columns in the Fort Worth Star Telegram at www.dfw.com/sports. |